|

|

|

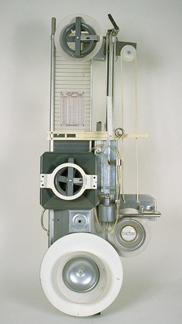

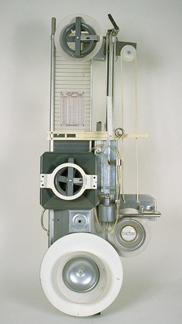

images: Ken Butler

Mark Laliberte / Pop Goes The Art-World:

An 8-Track Introduction (dam981003-01cd)©1998 Thinkbox Products. All Titles Published by Origin Obscure Music (SOCAN). Recorded in Canada.

Made in Detroit. All Rights Reserved. Unauthorized duplication and sampling of this recording is strictly prohibited.

Total Running Time (31:33)

TRACK 1 / A Slightly Relevant Quote (1:00)

"The syncopations and textures of dance music, through its complex polyrhythms and drum and bass patterns, has the ability to produce a grounded aesthetic of sensual pleasure and to literally move the body, both physically and emotionally."

TRACK 2 / Industry Marches On (4:35)

In many ways, popular music has become one of the principal defining cultural forces of our time. Mainstream music is present everywhere we go; it can be found in all walks of life, presented for both enjoyment during leisure and as a background track to the working day. This omnipresence makes the pop industry an influential force, driving a marketed youth culture and the interconnected youth fashion industries ever forward. The music industry itself has enforced the methods of this public consumption by harnessing musical and creative energies into packaged images and recordings, the primary product of the recording industry being the ever-popular compact disc. As a medium, the disc has the ability to provide its listener with a singular, intimate listening experience. It creates a one-sided dialogue between performer and patron. Within the realm of pop music, however, there exists little in the way of an alternate presentation, save perhaps the officially sanctioned 'live' concert that often accompanies the mainstream music release. In this age of entertainment mega-corporations, there seems to be no way to detach the musical experience from its well-engrained cultural position as a unitary commodity.

TRACK 3 / The Sounds of Life (2:03)

Audio Art is an often neglected facet of art practice. Defined largely by a predominant concern with providing new ways of looking at noise and the everyday sounds of life, audio artists have struggled for years with the dilemma of differentiating their productions from the productions created under the moniker of music. Using all manner of noise to penetrate the silence of official artistic expression, audio art has slowly developed against the grain of visual culture as an alternate way of communicating with an audience. More concerned with the sense of sound than sight, it has remained a somewhat misunderstood mode of artistic creation.

TRACK 4 / All Noise Is Music (4:26)

Ironically, if audio artists have had to continually struggle for acceptance within a fine arts context, their ideas have been openly embraced by musicians and composers in recent decades. In terms of providing the world-at-large with an expanded view of its musical language, the experiments of audio artists seem to have reverberated across the entire spectrum of the commercial music industry. In an essay studying the introduction and gradual acceptance of noise into the approved musical realm, cultural critic Chris Twomey refers to the 90's as the moment in time where "noise, whether electronically or acoustically produced, recorded environmentally or appropriated from the history of recorded sound, has become a major element in music, from the underground to the Top 30." As he tracks this change in the popular aesthetic, he notes that many of the recording artists responsible for introducing unconventional sounds and ideas to the world of music were actually responding to what they were hearing in the galleries, or in many cases were indeed former members of the art world that had migrated out of their audio and performance art backgrounds into the larger world of pop music.

TRACK 5 / Collapse of Now (5:11)

With this in mind, it could be argued that gallery-oriented sound art has had to respond to this accepted change in public perception. Now that everything from Luigi Russolo's Noise Organs, a series of instruments that imitated the noise of machines , to John Cage's 4'33", a compositional critique on silence, has been parasitically absorbed by the pop genre -- now that the concept-motivated ambient and industrial music movements have made their aural mark on the masses, and digital sampling technology has finally come of age -- it may be time for today's audio artist to admit that the struggle to outline the differences and similarities between sound, noise, silence, and music is over. The distinctive line of separation between these categories no longer exists, the barrier having collapsed under the weight of repetitive overlap. In today's acoustically-enriched environment, where all sounds are looked at as being ripe with potential, simple issues of difference are irrelevant. With the coming of the electronic age sound has been truly liberated, and today's audiences seem ready to absorb just about anything that can be pressed onto a CD. But how will this same audience respond to work created using a now-familiar language, yet made with the sole intention of presentation within the specific context and confines of the gallery system?

TRACK 6 / New Media Composers (4:32)

The ever-increasing importance of a hybridized music within the contemporary popular culture has contributed significantly to the ideas that drove this exhibition into existence. Detachable Music For A Collapsible Culture is presented as a gallery exhibition that focuses on a number of next-generation audio artists that use music as a source material to produce dynamic visual-based works of art. The works in this exhibition contain a distinct and predominant element of sound, yet steer away from the heightened sensitivity to abstract and ambient noise that has traditionally been associated with the genre of sound art; instead, these artists seem to favour a conscious and deliberate organization of sound that acknowledges a historical attachment to music. Most concerned with music's ability to speak to the masses, the artists represented by Detachable Music... do not compose in the traditional sense of the word, but instead use the structure and language of music as a point of reference to experiment with their audience's preconceptions, linking their work to concepts and ideas relevant to both contemporary art practice and the current state of the pop palette.

TRACK 7 / Music As Intellectual Shareware (6:29)

Through the mediated blanket of a product-heavy audioculture, the masses seem to have developed the ability to individually judge what they hear, to apply meaning and value to sounds, and to make listening choices based on personal taste. They are aware of all the genres and subgenres of the industry, possessing and referencing a sophisticated and diverse body of historical musical knowledge. In music, unlike in art, the masses seem to have developed a personal and participatory individual position. Audio artists everywhere have had to make value judgments about the nature of their work in relation to the mainstream audio industry, and have taken an interest in the potential of the well-informed audience this industry provides, searching for news ways to dialogue with the consumers of pop music and popular culture while still remaining outside of the entertainment sector. The artists in this show, though working from different areas of the world, have all chosen to incorporate the dominant global language expressed by a hybridized pop music into their artwork, to effectively transfer its energies and essence into a gallery-motivated context. They survey the pop stratum in a manner that presents knowledge of music as a kind of 'intellectual shareware' understood by all, save perhaps the deaf amongst us. By tapping into this common body of knowledge and taking advantage of the expanded language that a hybridized music now offers, the works represented in Detachable Music For A Collapsible Culture attempt to give new meaning to an art of sound. What the artists in this show produce through their very specific appropriations resonate with the power and poetry of the pop aesthetic, but also reflect a concern for critical environment that subverts the normal format of music as a commodity.

TRACK 8 / Institutional Listening Session (3:17)

Rather than exclusively exploring the limited presentation platform of the compact disc, fine artists using audio technology have also become aware of the need to supply a unique context and position for their creations, given the current state of humanity's inner ear. At this moment in time, only issues of context seem to determine whether a sound work will be labeled an artistic or musical experience. Recognizing popular music as a tremendously important site of common culture, Detachable Music...'s engagement with its audience within the particular social context of the gallery is an attempt at providing an alternate listening experience for the masses in hopes of detaching this experience from their common expectations. As this exhibition illustrates, works that exist as a kind of substitute musical expression might best be presented in new and often non-musical settings.

Recommended Readings:• ELECTRIC SOUND by Joel Chadabe. Prentice-Hall. 370 pages.

• THE ART OF NOISES by Luigi Russolo. Pendragon Press. 96 pages.

• OCEANS OF SOUND by David Toop.

• SOUND BY ARTISTS Edited By Dan Lander and Micah Lexier. Art Metropole. 385 pages.